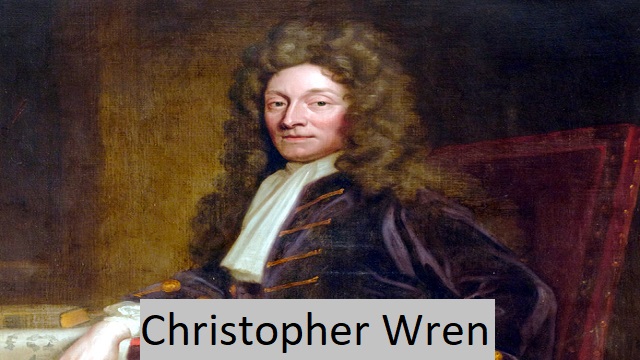

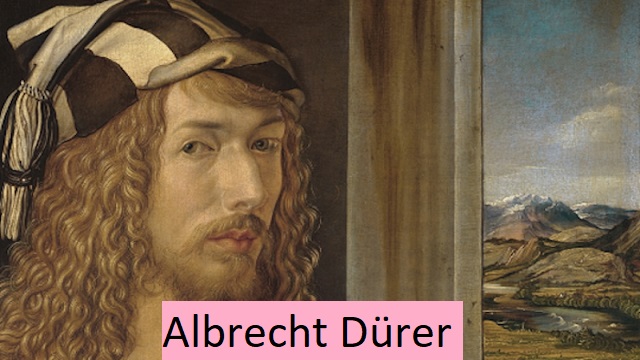

Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer (born May 21, 1471, Imperial Free City of Nuremberg [Germany] – died April 6, 1528, Nuremberg), painter and engraver generally regarded as the greatest artist of the German Renaissance. His vast collection of works includes altar pieces and religious works, numerous portraits and self-portraits, and copper engravings. His woodcuts, like the Apocalypse series (1498), retain a more Gothic flavor than the rest of his work.

Education and Early Career

Dürer was the second son of Albrecht Dürer the Elder, a goldsmith who left Hungary in 1455 and settled in Nuremberg, and Barbara Holber, who was born there. Dürer began an apprenticeship as a technical draftsman in his father’s goldsmith’s workshop. His precocious skills are evidenced by the remarkable self-portrait he painted in 1484 at the age of thirteen and the Madonna with Musicians, executed in 1485, already completed as works of late Gothic art. In 1486, Dürer’s father arranged for Dürer to be apprenticed to Michael Polgemus, the painter and woodcarver whose portrait he had painted in 1516. In 1490, Dürer completed the first known painting, a portrait of his father, which represents the distinctive style familiar to the mature master.

Dürer’s days as a traveler probably took the young artist to Holland, Alsace, and Basel, Switzerland. There he completed his first woodcut, St. Jerome the Healer of the Lion. In 1493 or 1494 Dürer stayed briefly in Strasbourg, and was again in Basel to make several illustrations for books. One of the masterpieces of this period is a self-portrait with forks drawn on parchment in 1493.

First trip to Italy

At the end of May 1494, Dürer returned to Nuremberg, where he soon married Agnes Frey, a merchant’s daughter. Apparently, Dürer made his first trip to Italy in the fall of 1494 and stayed there until the spring of 1495.

A landscape watercolor painting of the South Tyrolean Alps, produced on this trip, is one of Dürer’s best works. It represents a part of the landscape, skillfully chosen for its compositional value, in a crudely drawn location, rendered in broad strokes with a wonderful harmony of details. Dürer primarily used pure, cool and muted colors to suggest depth and atmosphere, although there was no contrast between light and dark.

A trip to Italy had a strong influence on Dürer. Direct and indirect references to Italian art can be found in most of his drawings, paintings and prints of the next decade. During his stay in Venice and probably before traveling to Italy, Dürer saw prints by Central Italian masters. He was most influenced by the Florentine Antonio Pollaiuolo for his studies of sinuous and energetic lines of the human body in motion, and by the Venetian Andrea Mantegna, an artist deeply concerned with classical subjects and the precise linear segmentation of the human body . Dürer’s secular, allegorical, and often egocentric paintings of this period are often adaptations of Italian models or entirely original creations inspired by the free spirit of the Neo-Renaissance. For Hercules and the Birds of Stymphalis, Dürer adapted the character of Hercules from Polivolo’s The Rape of Deianira. A purely mythological painting in the Renaissance tradition, Hercules is an exceptional example of Dürer’s work. The central panel of Dürer’s Dresden altarpiece, circa 1498, is stylistically similar to Hercules and shows influence from Mantegna. Most of Dürer’s free adaptations show the additional influence of the more lyrical and older painter Giovanni Bellini, whom Dürer met in Venice.

The most notable painting that shows Dürer’s development towards the Renaissance spirit is a self-portrait done in 1498. Here Dürer sought to convey the ideals of the Renaissance aristocracy in his portrayals. He liked the sight of a handsome, well-dressed young man who was quite boastful about his life. Instead of a classic, neutral monochrome wallpaper, it depicts an interior with a window opening to the right. The windows offer a small view of the mountains and the distant sea, a detail clearly reminiscent of contemporary Venetian and Florentine paintings. The focus on his figure inside the house separates his world from the vast landscape of distant scenery, another world to which the artist feels connected.

The Italian influence in Dürer’s graphics was slower than in his paintings and drawings. Strong late Gothic elements dominate the dreamlike woodcuts in his Apocalypse (Revelations) series, published in 1498. The woodcuts in this series show heightened expression, rich emotion, and cluttered, often overcrowded compositions. The same tradition influenced the early woodcuts of Dürer’s Great Passion series from about 1498. Nevertheless, the fact that Durler adopted a more modern conception, inspired by classicism and humanism, represents his fundamentally Italian leanings. Woodcut Samson and the Lion (c. 1497), Hercules Conquering Cacus, many engravings from the woodcut series The Life of the Virgin (c. 1497) 10-1500) has a distinctive Italian flavor. Many of Dürer’s engravings are in the same Italian style. Some of his examples that can be cited are Fortune (c. 1496), The Four Witches (c. 1497), and The Sea Monster (c. 1497). 1498), Adam and Eve (1504), and the Great Horse (1505). Dürer’s graphics eventually influenced Italian Renaissance art, initially in Dürer’s own work. However, his graphic style continues to fluctuate between Gothic Revival and Neo-Italian until about 1500. Then his unceasing efforts finally find a precise direction. It seems clearly rooted in Essolt Krell’s penetrating portraits, Portraits of Three Members of the Noble Tucher Family of Nuremberg – all from 1499 – and Portrait of a Young Man from 1500. In 1500 Dürer painted another self-portrait , a flattering and Christian image. During this period of consolidation of Dürer’s style, Italian elements in his art were reinforced by his contact with Jacopo di Barbara, a minor Venetian painter and printmaker looking for a geometric solution to depict human proportions; It was probably through his influence that around 1500 Dürer began grappling with the problem of human proportions in the manner of the Renaissance. At first the most concentrated result of his efforts was the great engraving of Adam and Eve (1504), in which he attempted to convey the mystery of human beauty in an ideal, intellectually calculated form. In all respects, Dürer’s art quickly became a classic. One of his most important classical works is the painting “Three Kings” (1504), created with the participation of students. Although the five-frame composition has an Italian character, Dürer’s intellect and imagination were more than directly dependent on Italian art. From this mature style, the bold, natural, and subdued impression of the central panel, “The Number of the Magi,” and the sophisticated, unconventional realism of the side panels, depicting drummers and musicians, and Job and his wife.

Albrecht Dürer’s second trip to Italy

In the fall of 1505 Dürer made his second trip to Italy, staying there until the winter of 1507. Again, he found most of his time in Venice. Among the Venetian artists, Durer has the greatest admiration for Giovanni Bellini, now the main master of early Venetian painting, who completed the transition from his later work to the High Renaissance. These Venetian-era portraits of dissolute men and women reflect the kind of gentle and tender portraiture of which Perini was particularly fond. One of Dürer’s most impressive small paintings of this period, the half-length compressed composition of “Young Jesus with the Doctors” of 1506, dates back to Bellini’s free adaptation of Mantegna’s “Presentation in the Temple”. Dürer’s works are virtuosic performances that display mastery and attention to detail. In this painting, the label of a book held by an old man in the foreground reads “Five Days’ Work”. Dürer had to complete this painstaking artistic rendering, which required detailed drawings, in less than five days. The portraits of a young man and a young woman, painted between 1505 and 1507, are of far greater artistic value than this rapidly completed work, which seems to bear a striking resemblance to Bellini’s style. These paintings have a warmth and lively expression that Dürer has rarely achieved, a flexibility of subject matter combined with a truly artistic technique. In 1506, in Venice, Dürer completed his large altarpiece, The Feast of Garlands of Roses, for the Cathedral of the Germans in the Basilica of San Bartolomeo. Later that year, Dürer made a short trip to Bologna before returning to Venice for the last three months. Dorir believes that Italy is in his artistic and individual home that the Venice displays the words in his last message (on 1506), Philippald Berkeheimer’s, his long -term human friend, his imminent return to Germany. For “o”. How long will I stay cold away from the sun. Here I am a noble man, a parasite at home. B

Development after the second Italian trip

At the end of it in February 1507, Durner returned to Nuremberg, where two years later got an impressive house (which is still found and kept as a museum). It is clear that the artistic impressions that his Italian journey gained continued to influence Dureer to employ classic principles in creating great original books. Among the paintings belonging to the period after his second return from Italy are the crowd scenes The Martyrdom of All (1508) and The Adoration of the Trinity (1511). The drawings of this period are reminiscent of Mantegna, and betray Dürer’s quest for the completion of classical forms through simple, densely modeled, flowing lines of fabric. Simplicity and majesty are even more characteristic of the doublet of Adam and Eve (1507), in which two figures stand calmly against a dark, almost naked background in relaxed classical poses.

From 1507 to 1513, Dürer completed the Passion series in copperplate engravings, and from 1509 to 1511 produced the Minor Passion series in woodcuts. Both of these works are characterized by a sense of space and a tendency toward stillness. In 1513 and 1514 Dürer produced the largest copper engraving, Night, Death and the Devil, Saint Jerome, and Melancholia I, in his studio. The extensive, complex, and often contradictory literature on these three reliefs is mainly concerned with their ambiguous and allusive iconographic details. Although repeatedly disputed, it is probably believed that the inscriptions should be interpreted together. However, there is agreement that Dürer wanted to maximize his artistic intensity with these three master engravings, which he succeeded in doing. The richness of the finished form and the imagination and mood merge into utter classic perfection. Dürer’s most expressive portrait of his mother belongs to the same period.

Service to Maximilian I by Albrecht Dürer

While in Nuremberg in 1512, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I recruited Dürer into his ranks, and Dürer continued to work primarily for the Emperor until 1519. He collaborated with many of the greatest German artists of the time on a series of marginal notes for the Emperor’s Prayer Book. He also made a number of iron engravings (between 1515 and 1518) which demonstrate his mastery of the medium and his imagination. These pleasant improvisations are contrasted with monumental woodcuts full of panegyrics made for Maximilian. With these rather extravagant woodcuts, Dürer had to make an effort to adapt his creative imagination to the psyche of the client. As well as a number of formal exhibits – a painting titled Lucretius (1518) and two portraits of the Emperor (c. 1519) – Dürer created a number of more informal paintings of considerably greater appeal over the course of of this decade. He also traveled. He stayed in Bamberg in the fall of 1517. Martin Luther had published 95 theses the previous year denouncing the sale of papal indulgences. (See scholar’s note.) Dürer later became a devoted follower of Luther. In 1515 Dürer achieved worldwide fame as an artist. It was then that he exchanged works with Raphael, the leading painter of the Renaissance.

Read also: Francesco Borromini