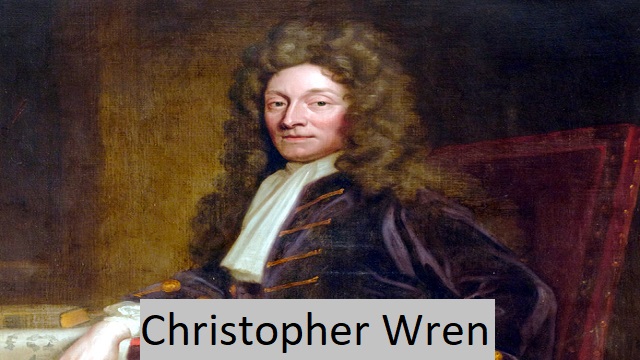

Christopher Wren

Christopher Wren, full text Sir Christopher Wren (born 20 October 1632 in East Noyle, Wiltshire, England; died 25 February 1723 in London), designer, astronomer, surveyor and the greatest British architect

of his time. Wren designed 53 London churches, including St Paul’s Cathedral, and many notable secular buildings. He was one of the founders of the Royal Society (President 1680-1682), and his scientific work was highly regarded by Isaac Newton and Blaise Pascal. He was knighted in 1673.

Early academic career and scientific activity

Ren was the principal’s only surviving son and suffered from poor health from an early age. Before Christopher was three years old, his father was appointed Dean of Windsor and the Wren family moved into the Courtyard. It was among the intellectuals around King Charles I that the boy first developed a sporting interest. Windsor’s life was thrown into chaos by the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642. The Dean was dismissed and the Dean was forced to retire, first to Bristol and then to his son-in-law William Holder’s country home in Oxfordshire. Wren was sent to school at Westminster but spent much of his time teaching Holder and experimenting with astronomy. He translated William Oughtred’s work on sundials into Latin and built several astronomical and meteorological devices. Although the general direction of his studies was toward astronomy, there was an important turn to physiology in 1647 when he met the anatomist Charles Scarburgh. Wren designed experiments for Skarberg and built models that represented muscle action. One factor that stands out clearly in these early years is Wren’s desire to approach scientific issues through visual means. His surviving figures are beautifully drawn, and his models look equally elegant.

In 1649 Wren entered Wadham College, Oxford as a ‘gentleman’, obtained a privileged position and graduated with a B.A. 1651. At the time, Oxford was undergoing a stringent purge of the more conservative elements by the Parliamentary government. New people were brought in, some of them extremely capable, and they showed a particular interest in the “experimental philosophy” eloquently heralded by the philosopher of science Sir Francis Bacon. Wren received his MA in 1653, was elected to All Souls College, Oxford that year, and began an active period of research and experimentation, culminating in his appointment in 1657 as Gresham Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College, London. Receipt. The following year, with the death of Oliver Cromwell and the ensuing political upheaval, the army occupied the college and Wren returned to Oxford, where he probably remained through the events leading up to the reinstatement of Charles II in 1660. He returned to Gresham College, where he resumed academic activity and proposed an association think tank to “promote the experimental study of physics and mathematics.” With the support of the restored monarchy, the group became the Royal Society and Wren was one of his most active participants and wrote the preface to its charter.

In 1661 Wren was appointed Savirian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford University, and in 1669 Charles II’s Investigator. But despite being successful in many fields, the 30-year-old still seems to have yet to find something that he can be completely satisfied with.

Switch to architecture

One reason for Wren’s turn to architecture may have been the almost complete lack of serious building endeavors in Britain at the time. Architect Inigo Jones passed away about 10 years ago. There were perhaps half a dozen men in England who had a reasonable understanding of architectural theory, but none had the confidence to bring architecture into the intellectual realm of the Royal Society’s idea – that is, to develop it as an art capable of useful scientific research. , , Given the opportunity it was the perfect field for Wren to master—a field where the intuition of a physicist and the art of a modeller unite to design works of monstrous size and complex structure. Opportunity came, for in 1662 he was involved in the design of the Sheldonian Theater at Oxford. Such was the gift of Gilbert Sheldon, Bishop of London, for his old university, to be a stage in the classical sense, where the functions of the university were held.

It followed a classical form, inspired by the ancient theater of Marcellus in Rome, but newly designed, combining a classical perspective with experiential modernity in a manner entirely characteristic of the spirit of the Royal Society. Reimagined with reinforced wooden trusses. At the same time, Sheldon was supposedly discussing with Wren about the battered – and partly largely abandoned – St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Therefore, Ren was deeply and immediately attracted to design problems. What he badly needed at the time was contact with classical European tradition, and he jumped at the opportunity to join the embassy in Paris. In 1665, the architecture of the court of Louis XIV reached a height of creativity. The Louvre was nearing completion and the renovation of the Palace of Versailles had begun. Jean Lorenzo Bernini, also a great sculptor and architect, designed the eastern facade of the Louvre in Paris. The old Italians allowed Wren to see his drawings. There was much more for Rennes to see in the French capital, including the domed churches of Val de Grasse and Solbonne, and gorgeous castles within easy reach of Paris. At Oxford in the spring of 1666 he designed the first dome for St Paul’s Cathedral. It was originally accepted on August 27, 1666. But a week later, London was on fire. The Great Fire of London burned two-thirds of the city and destroyed the old St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Wren was probably in Oxford at the time, but the news, so extraordinarily relevant to his future, immediately drew him to London. Between September 5 and 11, he identified the precise area of destruction, drew up a plan for the reconstruction of the city along new and more regular lines, and presented it to Charles II. His plan reflected his familiarity with Versailles and his knowledge of Rome by Pope Sixtus V through inscriptions. Others also submitted plans and the king announced on 13 September that a new plan for London would be adopted. But the new plan did not go beyond the finished paper. The problems of investigation, compensation and redistribution were enormous. The Restoration Act was passed in 1667. The Act only authorized the widening of some roads, set standards for building new houses, imposed a tax on coal entering the Port of London, and provided for the restoration of some essential buildings. In 1669 the King’s Lands Surveyor died and Wren was soon installed. In December he married Faith Coghill, moved into the surveyor’s official residence at Whitehall, and is known to have lived there until his dismissal in 1718. A second Reconstruction Act was passed in 1670 and increased the coal tax, which funded the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral and several churches in the City of London, and the erection of memorial columns (monuments). fantastic fire.

The city was now rebuilding at a decent pace. Ren himself has nothing to do with the general process. He did not design houses or warehouses for city businesses, but occasionally advised city authorities on large-scale projects. He was the king’s surveyor working from Whitehall, not an official in the City of London. St. Paul’s and the city’s churches did not automatically fall within the realm of royal works, although there was a long tradition of royal responsibility for St. Paul’s. In 1670 the first churches were rebuilt. Eighty-seven churches were destroyed in the fire, but few were united so that only 52 could be rebuilt. Ren was personally responsible for all of these, but each did not represent his fully developed designs. That there were many commissions is indicated by the existing drawings. Only a few are in Ren’s hands. There is no doubt, however, that Wren fully approved of the design, and some churches bear his emblem.

Construction of St. Paul

While the church was being built, Wren slowly and painfully developed a design for St. Paul. The early stages are represented by the first model from 1670, now in the trophy room of the cathedral. The plan was approved by the king and the demolition of the old cathedral began. However, in 1673 the design seemed too modest, and Wren met his critics with a grander design. Then a wooden model was made and a so-called large scale model is kept in São Paulo. However, he failed to meet the canons of St. Paul and general spiritual doctrine, forcing Ren to abandon his ideals and compromise with tradition. In 1675 he proposed a rather poor design in the classical Gothic style, which was quickly accepted by the king, and construction began within months.

What happened next is a mystery. The cathedral that Wren began building bears a slight resemblance to Warrant Design. A mature and beautifully detailed structure begins to rise. By 1694 the masonry of the chancel was completed and the rest of the paste was at hand. In 1697, the first services took place in the cathedral. But there was still no dome. The construction work has been going on for 22 years, and it seems some uneasy elements within the government have dragged it on for far too long. As an incentive for faster progress, half of Wren’s salary was withheld until the cathedral was completed. Wren was now 65 years old. Construction was completed in 1710 and in 1711 the completion of the cathedral was officially announced. Raine, 79, has filed a request for withholding of part of his duly paid salary. The cathedral was built under the supervision of a single architect for 35 years. (See also St. Paul’s Cathedral and related classical articles in the Encyclopædia Britannica Second (1777–84) and Third (1788–1797) eds.)

Competing projects

During this time, Wren was not only the chief architect of St. He Paul’s Church and the City, but was also responsible for the King’s works and therefore for all expenditures issued by the State Treasury. Although there was a staff to carry out regular maintenance, much of the work fell into their hands, including the management of the building developments in and around Westminster. Around 1674, the University of Cambridge considered building a Senate House for the same purpose for which the Sheldonian Theater was built. Ren created the design, but the project was abandoned. The master of Trinity College, who promoted this plan, was disappointed, but persuaded his college to create a new library (1676-1684) and use Wren to design it. Ren’s classics are impressive here. There are no traces of the Baroque style that was popular in Europe at the time, so the building could be mistaken for a Neoclassical work of a century later.At Oxford in 1681, the Dean of Christ Church invited Wren to complete the college gates. The lower part of Tom’s Tower, known as the City Gate, was built in richly decorated Gothic style by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. The octagonal tower imposed by Wren shows both his respect for Gothic and his doubts about it. His attitude towards Gothic design was consistent and influenced Gothic architecture in England well into the 18th century. In 1682 Charles II established the Royal Hospital at Chelsea to treat veterans of the standing army. While undoubtedly an idea drawn from Louis XIV’s Hôtel des Invalides in Paris (1671–76), the Lenn Building, completed around 1690, differs greatly from the original. Charles II died in 1685. During the short reign of his brother James II, Wren’s attention was mainly directed to Whitehall. The new king, a Roman Catholic, wanted a new chapel. He also commissioned a new private gallery, council chamber and riverside apartment for the queen. All of these were built by Warren but were destroyed in the Whitehall Fire of 1698.Not much information about Wren’s personal life after 1669 is available. He was ennobled in 1673, the year of the Great Model. His first wife died of smallpox in 1675, leaving him with a young son, Christopher (the other died in infancy). His second wife, Jane Fitzwilliam (Fitzwilliam), had a daughter, Jane, and a son, William, who died in 1679.During these years he never completely abandoned his scientific activity. He was still head of the Royal Society and was President from 1680 to 1682. He was sufficiently active in public affairs to return as Member of Parliament for Old Windsor in 1680, and though never took the seat again in 1689 and 1690. With the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which dethroned James II, Wren became William of Orange’s chief architect. Willem III and Maria II turned out to be the most active builders of all. They disliked the Palace of Whitehall and in 1689 Wren was working to rebuild the two palaces. One is in Kensington outside London, and the other is at Hampton Court, 15 miles (24 km) up the River Thames. Kensington Palace is a minor renovation of the old house with the addition of a new court and gallery. The south facade, although not a perfectly satisfactory structure, is a well-assembled piece of brick. Hampton Court Palace, on the other hand, began as a larger-scale project than Wolsey’s complete reconstruction of the palace. Wren’s early designs survive, showing him spreading his wings as palace architect for the first time.However, it was decided that only half of the old palace should be demolished, and Wren’s design was severely curtailed. However, he did make many innovations and unique use of English building materials. Hampton Court is a mixture of red and gray brick and Portland stone combined in excellent balance.Queen Mary died in 1694. The king lost his mind and the construction of Hampton Court was halted. The palace was only completed in 1699. Two years before her death, the Queen began plans to build a royal hospital for sailors in Greenwich. This is why Wren made the first plan in 1694. Work began in 1696, but all the buildings were not completed until several years after his death. Greenwich Hospital (later the Royal Naval College) was Wren’s last major work and the only one still going on after the completion of St. Paul’s in 1710. Queen Anne gave him a house at Hampton Court. He also owned a London house in the rue Saint-James, and one evening after supper a servant found him dead in an armchair, noting that he was taking an unusually long nap. Wren was buried with really gerat ceremony in St. Paul’s Cathedral, the tomb covered with a simple carved slab of black marble. His son later made a dedication on a nearby wall, including a phrase that would become one of the most famous monumental inscriptions: “).

The legacy of Christopher Wren

Rin was 90 years old at the time of his death. Even the men he trained, who owed much to his original and inspiring leadership, were no longer young. The Baroque school he had already created was being attacked by a new generation who had put Wren’s reputation aside and looked beyond Inigo Jones. Eighteenth-century architects could not forget Wren, but could not forgive the unclassical elements of his work. The church left its strongest mark on later architecture. In France, where English architecture rarely made much of an impression, St. Paul’s Cathedral could not easily be overlooked, and the Church of St. Genevieve (now the Panthéon) in Paris, begun about 1757, on a drum and dome. It is similar to that. San Paulo by bridge. No one with a dome to build can ignore Wren, and there are countless versions, from St. Isaac’s Cathedral (dome built 1840-1842; completed 1858) in St. Petersburg to the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. Si (dome built in 1855-63). It was not until the turn of the 20th century that Wren’s work became a powerful and sometimes controversial element of British architectural design. The last great architect to admit to having trusted him was Sir Edwin Lutyens, who died in 1944. The Wren Society was founded in 1923 on the 200th anniversary of Wren’s death by A.T. Bolton and H.D. Hendry.

Read also: Albrecht Dürer