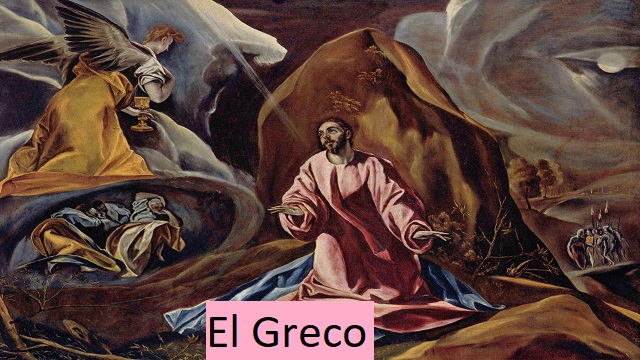

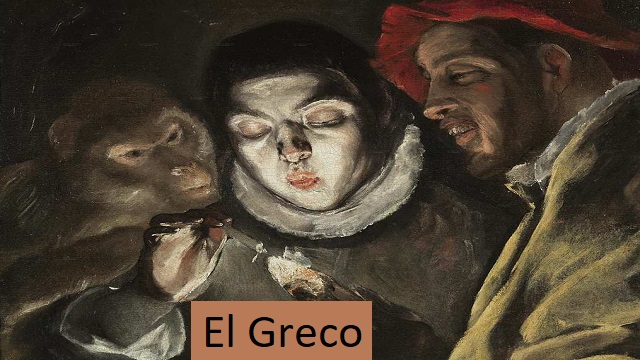

El Greco

Castle of Domenicos Theotokopoulos El Greco (b. 1541 Candia [Iraklion], Crete – d. 7 April 1614, Toledo, Spain), master of Spanish painting. 20th century assessment. Also worked as a sculptor and architect.

Early life and works

El Greco never forgot that he was of Greek origin and signed his paintings with his full name, Dominicus Theotokopoulos, usually in Greek letters. Nevertheless, he is commonly known as El Greco (the Greek), a name he acquired while living in Italy, where it was common to identify people by their country or city of origin. However, the particular form of the article (El) most likely comes from the Venetian or Spanish dialect.

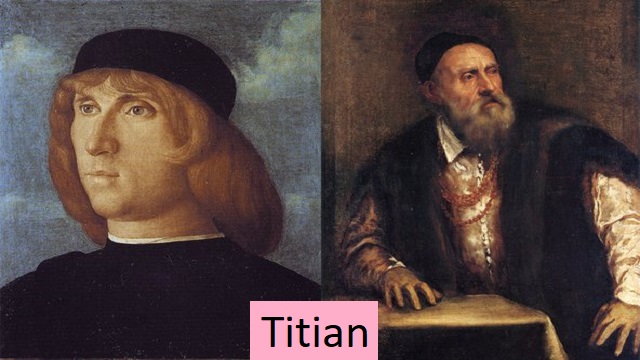

His native Crete was Venetian property at the time and he was a Venetian citizen, so he decided to study in Venice. The exact year of this event is not known.However, estimates place it between 1560 and 1566, when he was 19 years old. In Venice he entered the studio of Titian, the greatest painter of his time. Information about El Greco’s years of residence in Italy is limited.On November 16, 1570, Giulio Clovio, a publisher in the employ of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, wrote a letter requesting a stay in the Farnese palace for “a young man from Candia, a pupil of Titian”. On July 8, 1572, in a letter from Rome to the same cardinal, a Farnese official wrote a “Greek painter” is mentioned. Soon after, on September 18, 1572, “Dominico Greco” paid his dues to the Guild of Saint Luke in Rome. It is not known how long the young artist stayed in Rome, but he may have returned to Venice between 1575 and 1576 before leaving for Spain. Some of El Greco’s paintings in Italy are entirely in the 16th-century Venetian Renaissance style. No influence of Byzantine heritage is visible, except perhaps in the elderly faces. For example, Christ heals the blind. The placing of the figures in deep space and the emphasis on the architectural setting, in the style of the High Renaissance, is particularly notable in his early paintings, Christ Cleansing the Temple. The first evidence of El Greco’s exceptional talent as a portrait painter in Italy appears in the portraits of Giulio Clovio and Vincentio Anastaghi.

Middle Years

El his Greco first appeared in Spain in the spring of 1577, first in Madrid and then in Toledo. One of the main reasons he sought a new job in Spain was that he was aware of Felipe II’s great project to build the Convent of San Lorenzo in El Escorial, about 42 km northwest of Madrid. No doubt. In addition, the Greeks must have met important Spanish clergy in Rome through Fulvio Orsini, humanist and librarian of the Farnese palace. that at least one Spanish cleric, Luis de Castilla, who spent some time in Rome during this period, became a close friend of El Greco and was eventually appointed one of the executors of the will; a favour. Luis’ brother, Diego de Castilla, gave El Greco his first order in Spain, which may have been promised before the artist left Italy.

In 1578, the only son of the painter, Jorge Manuel, was born in Toledo, a descendant of Dona Jeronima de las Cuevas. She seems to have been spared by El Greco, and although he acknowledged her and his son, he never married her. This fact baffled all writers as he mentioned it in several documents including his will. It is possible that El Greco was married in Crete or Italy in his unhappy childhood and thus cannot justify another engagement.

El Greco lived in Toledo for the rest of his life, busy with duties there and in the local church and monastery. He became close friends with leading humanists, scholars and clergymen. Antonio de Covarrubias, son of the classical scholar and architect Alonso de Covarrubias, was a friend with whom he painted portraits. Fray Hortensio Paravicino, rector of the Church of the Holy Trinity in Spain and a favorite preacher of Philip II of Spain, dedicated four sonnets to El Greco, one of which included a portrait of the artist himself. Luis de Góngora y Argote, one of the most important literary figures of the late 16th century, composed a sonnet on the painter’s tomb. Another writer, Don Pedro de Salazar de Mendoza, belonged to the most intimate circle of El Greco’s entourage. The lists compiled after his death confirm that he was a man of exceptional culture, a true Renaissance humanist. To give an idea of the breadth and scope of his interests, his library contains works by major Greek authors in Greek, several books in Latin, and others in Italian and Spanish. Bible in Greek, Minutes of the Council of Trent, and Architectural Treatises by Marcus Vitruvius Beaulieu, Giacomo da Vignola, Leone Battista Alberti, Andrea Palladio, and Sebastiano Serlio. El Greco produced a Vitruvius version with illustrations, but the manuscript has been lost.

From 1585 and onwards, El Greco lived in the noble late-medieval palace of the Marquis de Villena. Although it is near the now-ruined Palazzo Villena, the Toledo Museum, named Casa y Museo del Greco (“El Greco’s House and Museum”) was never his residence. He probably needed space for his laboratory more than a life of luxury. In 1605, the palace was designated by the historian Francisco de Pisa as one of the most beautiful in the city; It was not a pitiful crumbling structure, as some romantic writers assumed. El Greco certainly lived in considerable comfort, even if he did not leave a large fortune when he died. El Greco’s first commission in Spain was for the high altar and two side altars of the convent church of Santo Domingo el Antigo in Toledo (1579-1577). Never before had an artist received such an important and extensive commission. Even the architectural design of the altar frame, reminiscent of the style of the Venetian architect Palladio, was prepared by El Greco. The painting on the high altar, the Ascension of the Virgin, also marks a new period in the artist’s life and fully reveals his genius. Figures come to the fore and, in the case of the Messengers, a new sparkle of colour. The technique remains Venetian in the application of color and the free use of white light. But the treatment of contrasts, close to the intensity and dissonance of color, is clearly El Greco’s. For the first time the significance of his appropriation of Michelangelo’s art appears, particularly in the painting of the Trinity at the top of the high altar, where the powerfully sculpted body of the naked Christ leaves no doubt as the source ultimate. of inspiration. Also in the side altar of the Resurrection, the postures of the standing soldiers and the contraposto (a posture in which the upper and lower body are in opposite directions) of the golden figures are clearly inspired by Michelangelo.

At the same time, El Greco created another masterpiece of amazing originality – the Exolio (Undressing Christ). By drawing the composition vertically and compactly in the foreground, he seems moved by the desire to show the oppression of Christ at the hands of his cruel executioners. He chose a method of eliminating space common to mid- and late-16th-century Italian painters known as Mannerists, and is perhaps reminiscent of late Byzantine paintings in which the row-by-row correspondence of heads was used to depict crowds. The original gilded wood altarpiece that El Greco designed for the painting has disappeared, but the small sculptural group of the Miracle of Saint Ildefonso is still in the lower center of the frame. El Greco’s tendency to elongate the human figure is most evident at this time, for example in the handsome and unreconciled Saint Sebastian. The same extreme stretching of the body can also be found in the works of Michelangelo, in the paintings of the Venetians Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, and in the art of the most important Mannerist painters. The delicacy of Christ’s long body, heightened against the dramatic clouds of the crucifixion with the donors, foreshadows the artist’s later style.El Greco’s relationship with the court of Philip II was short and unsuccessful. The first is The Allegory of the Holy League (Dream of Philip II; 1578-1579) and the second is The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice (1580-1582). This last painting did not meet the king’s approval, and the king immediately ordered that another work on the same subject be replaced.Thus ended the relationship between the great artist and the Spanish court. The King is probably hampered by an almost shocking glow of yellow, unlike the ultramarine blues of the painting’s main group costume, which includes St. Maurice in the center. El Greco’s bold colors, on the other hand, are particularly appealing to the modern eye. Showcase the colors of the shapes and brushes to create a free and dreamy space and Venetian atmosphere.The Burial of the Comte d’Argaz (1586–1588) is considered El Greco’s masterpiece. Above, the allegorical vision of Gloria (“Heaven”) and the impressive pictorial arrangement represent all facets of this extraordinary genius’s art. El Greco made a clear distinction between heaven and earth. The sky above is like icy clouds, semi-abstract in form, and the adults are tall and ghostly. Below everything is the scale and proportions of the figures normal. According to legend, St. Augustine and Stephen miraculously appeared to lay the Comte de Argas in his tomb as a reward for his generosity to the Church. Dressed in gold and red, they bow reverently over the count’s body in magnificent armor that mirrors the yellow and red colors of the other figures. The boy on the left is El Greco’s son, Jorge Manuel. The handkerchief in his pocket is engraved with the artist’s signature and the date 1578, the year the boy was born. The men attending the funeral were prominent members of Toland society in the 16th century. El Greco’s Mannerist compositional style is never more clearly expressed than here. All the action here takes place in the front.

El Greco’s Later Years and Works

From 1590 until his death, El Greco’s paintings were astounding. His depictions of churches and monasteries in the Toledan area include the Holy Family and Magdalena, the Holy Family and St. Anne. He repeated several iterations of Agony in the Garden, whose strange forms and bright, cold, contrasting colors evoke a supernatural world. The pious theme of Christ carrying the cross is known from El Greco’s 11 originals and many manuscripts. El Greco represents most of the great saints, often repeating the same composition: Saint Dominic, Mary Magdalene, Saint Jerome Cardinal, Saint Jerome Penitent and Saint Peter Weeping. However, Saint Francis of Assisi was the artist’s favorite saint. About 25 originals depicting St. Francis survive, along with over 100 pieces of followers. The most popular of the several types were Saint Francis and Friar Leo meditating on death.Two large series of his (Apostrados) depicting Christ and the Twelve Apostles on 13 canvases are extant, one in the sacristy of the Cathedral of Toledo (1605-10) and another in his One unfinished (1612-14) is in El Greco’s House and Museum in Toledo. The frontal pose of Christ the Blessed in this series suggests a medieval Byzantine figure, although the color and brushwork are El Greco’s personal play on Venetian technique. In these works, the devotional intensity of the mood reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain in the Counter-Reformation era. Although of Greek origin and Italian by artistic training, the artist immersed himself in the religious milieu of Spain and became the most important visual representative of Spanish mysticism. However, the fusion of these three cultures has made him a unique artist who does not belong to any traditional school, and a unique genius with unprecedented emotional power and imagination. El Greco received several large commissions in the last 15 years of his life. three paintings (1596–1600) for the Colegio de Doña Maria de Aragon, an Augustinian monastery in Madrid; and the high altar, four side altars, St. Paul for the Hospital de la Caridad (1603-1605) in Illescas. Illustrated by Ildefonso.

Extreme deformation of the body was characteristic of El Greco’s later work. An example of this is the Adoration of the Shepherds painted in 1612-14 for his burial chapel. Brilliant kaleidoscopic colors, exotic shapes and poses create a sense of wonder and ecstasy, as shepherds and angels celebrate the miracle of a newborn baby. The Unfinished Vision of St. El Greco’s imagination in John makes him defy more of the laws of nature. The huge, wobbly figure of Saint John the Evangelist, dressed in abstractly painted blue-blue, reveals the souls of martyrs crying out for salvation. Similarly, the figure of the Immaculate Conception (1607-1614), originally in the church of San Vicente, rises into the sky in an explosion of ecstasy supported by large distorted angels. The spectacular views of Toledo below, abstractly rendered, are awe-inspiring with their ghostly glow of moonlight, while the rose and lotus clusters, symbolizing virgin purity, stand out in their pure beauty. it is perfect.

In the remaining three landscapes, El Greco showed his characteristic tendency to dramatize rather than portray. View of Toledo (ca. 1595) depicts a stormy, menacing, and passionate city with the same dark and foreboding clouds that appear in the background of his earlier Crucifixion with Donors. Painting in his studio, he arranged the buildings depicted in the picture according to the purpose of his composition. The View and Plan of Toledo (1610-14) is almost like a landscape, with all the buildings in dazzling white. An inscription by the artist on the highly fanciful canvas states that he placed the San Juan Bautista Hospital on a cloud in the foreground for better visibility, and the map in the photo shows the streets of the city. On the left, the Tagus River encircling Toledo, a city built on rocky hills, symbolizes the gods. El Greco lived in Italy and Rome itself, but seldom used such classical Roman motifs.

The only painting by El Greco with a mythological theme beloved by most Renaissance artists is Laocoon (1610–14). In the case of ancient Troy, he substituted a scene from Toledo, as just discussed, and showed little respect for the classical tradition by painting the body of a very expressive, but tall, massive priestess. Although El Greco was primarily a painter of religious subjects, his paintings, though few in number, are of a uniformly high quality. Two of his best later works are Fray Felix Hortensio Paravicino (1609) and Cardinal Don Fernando Niño de Guevara (c. 1600). Both are seated, as was customary for post-Raphaelite portraits of important clergymen. A Trinity monk, orator and renowned poet, Pallavicino is portrayed as a sensitive and intelligent man. The pose is essentially frontal, with the white fringe and black coat providing a very effective pictorial contrast. Cardinal Niño de Guevara, clad in crimson robes, is almost thrilled by his regular’s essential energy to command. The portrait of El Greco by Jeronimo de Cevallos (1605–10), on the other hand, is very sympathetic. The work is half length, finely colored and limited to black and white. The voluminous, then fashionable collar frames the generous face. With such a simple tool, this artist created a memorable characterization that places him next to Titian and Rembrandt in the highest rank of painter.

After El Greco’s death in 1614, there was no significant following in Toledo. His son and some unknown painters produced poor copies of the master’s works. His art was so personal and unique that he couldn’t bear his death. In addition, the new Baroque styles of Caravaggio and Carracci soon superseded the last surviving features of the 16th-century style.

Read also: Tintoretto