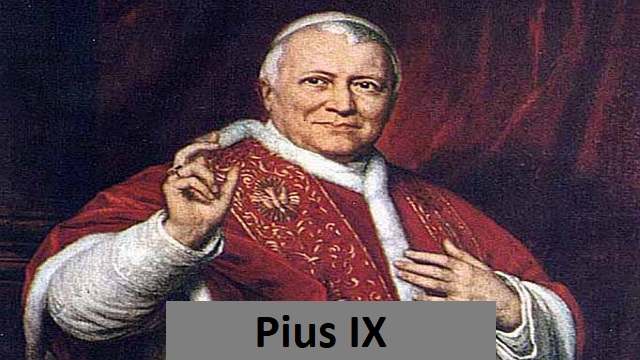

Pius IX, whose full name was Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church during the longest pontificate in history (1846–1878; born May 13, 1792 in Senigallia,Papacy; passed away in Rome on February 7, 1878; beatified on September 3, 2000; feast day on February 7).His reign saw the establishment of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception (1854), the Syllabus of Errors (1864), and the First Vatican Council sessions (1869–1870), which saw the official definition of the doctrine of papal infallibility.

Prepontifical life and early reign

The countess Caterina Solazzi and Girolamo Mastai-Ferretti’s fourth child, Pius IX, was the gonfalonier of Senigallia. During the turbulent revolutionary period of 1827 to 1832, he first rose to prominence as the archbishop of Spoleto. He was appointed bishop of the significant diocese of Imola in 1832, but it wasn’t until 1840 that he was given the title of cardinal priest of Saints Piero and Marcellino that he was presented with the hat.He was not the most well-known liberal candidate who stood a chance of succeeding Gregory XVI in 1846, but it only took the conclave two days to decide his election and thwart that of the conservative Luigi Lambruschini. In honor of Pius VII, a friend of his who had served as bishop of Imola like him, he chose the name Pius.The decision was somewhat prophetic because “Pio Nono,” like his predecessor, started out in life as a liberal supporter before bitterly learning that liberals frequently had anti-clerical tendencies. All of this, however, was still in the distant future in 1846, and the unusual spectacle of a liberal pope had all of Europe in a frenzy.The new pope was faced with a challenging circumstance. The Papal States were seen throughout Europe as urgently needing reform, with the possible exception of Metternich of Austria. Councils should be elected to help with local government, according to a memorandum from the French, English, Austrian, Russian, and Prussian ambassadors in Rome from 1831. A central body, made up partially of elected representatives, was also suggested.Finance should be under control, and the clergy’s hegemonic role in government and the legal system should end. Throughout Gregory XVI’s pontificate, the liberal viewpoint held fast to these actions as being absolutely necessary. Italian nationalists also frequently attacked the papacy because they saw it as one of Austria’s tools for retaining its dominance.

The Revolutions of 1848

The year of revolutions got underway in Sicily; before long, all of Europe was on fire, and Pius was confronted with demands that went far beyond what he had been willing to meet (see Revolutions of 1848). He was forced to approve a constitution on March 14 that established a two-chamber parliament with complete legislative and fiscal authority and the pope’s personal veto as the only check.Charles Albert of Sardinia declared war on Austria on March 23. In his address to the cardinals on April 29, Pius claimed that he was an impartial observer of the revolutionary activities sweeping Italy and that his reform agenda was merely the realization of the agenda that had been long imposed upon the papacy by the powers. Pius continued to try to steer a middle course for a while.Such sentiments were perceived as showing utter hostility toward the national cause in the atmosphere of the time, and the papacy was never again able to project itself as anything other than a reactionary bulwark in Italy.

Pius agreed to the appointment of popular ministries to stop a revolution from occurring in Rome itself, but none of the new ministers were able to maintain order.On November 15, one of them was murdered as a result of a rapidly deteriorating situation. When the Swiss guards were disbanded, a radical ministry was appointed, and the pope was effectively imprisoned. On November 24 and 25, he escaped to Gaeta in the kingdom of Naples with the assistance of the French and Bavarian ambassadors. Elections for a constituent assembly were held while he was away;This signaled the end of temporal power on February 9, 1849, and the establishment of a democratic republic. The papacy then made a formal plea for help to the leaders of France, Austria, Spain, and Naples. Although it was generally believed that the restoration of the pope could only happen with some sort of commitment to keep the Papal States’ government in place,and despite the fact that Louis-Napoléon, the recently elected president of France, supported such a policy, Pius resisted making any concessions and affirmed his determination to exercise his temporal power without any limitations at all.Pius returned to his capital on April 12, 1850, as a result of a series of military and diplomatic maneuvers by France and Austria that resulted in the unconditional restoration of papal rule.

The Roman question

It has frequently been claimed that Pius had changed since leaving Rome and was now a narrow reactionary. There is no doubt that his policy had changed, but his underlying attitude remained the same. He had always prioritized the needs of the church.He had been willing to accept nationalism and liberalism as long as they preserved the church, but experience had taught him that both led to revolution, which he had never been willing to accept. As a result of his political concessions, his spiritual power had come under attack, and he believed the only way to defend it was for him to continue using his temporal power.authority. It is understandable why Pius felt obligated to resist any change to his status as a temporal ruler once these two facets of his dominion had become inextricably linked.