Tintoretto

Tintoretto, nicknamed Jacopo Robusti (born c. 1518 in Venice [Italy] – died 31 May 1594 in Venice), the great Italian Mannerist painter of the Venetian school and one of the most important artists of the late Renaissance I am a person. Includes Vulcan Surprising Venus and Mars (c. 1555), The Mannerist Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (c. 1555). 1545-48), and his masterpiece of 1592-1594, The Last Supper at San Giorgio Maggiore. Increasingly interested in the drama of light and space, he was successful in his mature works (e.g. Praise of the Golden Calf, c. 1560) a brilliant dream quality.

Background and early years

Little is known about Tintoretto’s life. In his 1539 will he refers to himself as a liberal professional – an unsurprising description given his influential and powerful figure. No documents relating to Jacobo’s artistic training have survived. His biographers, including Carlo Ridolfi, who published a book in 1648, tell of his apprenticeship with Titian. On the other hand, contemporaries point out that Tintoretto’s style was shaped by the study of Tuscan formal elements, particularly Michelangelo’s, and pictorial elements derived from Titian. Most likely, Jacopo’s precocious talent prompted his father to place him in the workshop of a mediocre painter, but with an established tradition of craftsmanship, so that his son could learn the basics of his craft. Traces of pure style in his early works tend to confirm this hypothesis. But he soon came up with a different approach from the one we’ve tried, which was already quite unlike the style of Giorgione, who was active in Venice from 1530 to 1540, and who was the first to fuse forms and add local colors to their penetrating colors. Was about to subjugate colors. found it.

After the sack of Rome by imperial troops, the Roman artist’s emigration to Venice in 1527, and later contact with Tuscan and Bolognese painters, Venetian painters led to greater plasticism without changing the original color qualities. Venetian tradition. The influence of Michelangelo, the art historian and biographer Giorgio Vasari’s visit to Venice in 1541, and the trips of Venetian artists to central Italy completely renewed Venetian painting, providing appropriate means of expression for different types of imagery. In the revised idiom, forms and colors were mixed, and light prevailed, expressing a rich, fantastical, fantastical spirit. Thus, Tintoretto’s early works were influenced by all these influences. Critics identified a group of Tintoretto’s younger works, particularly the Sacre Conversazioni. One of these was painted in 1540 and shows a statue of the Virgin with a baby on her lap and six saints with their backs. The style reflects various elements of Venetian art from Tintoretto’s time, but shows a clear Michelangelo influence.

Career

Tintoretto’s first phase consists of a group of 14 octagonal ceiling panels with mythological motifs (originally painted for a Venetian palace), demonstrating a unique perspective sophistication and narrative clarity. Among other influences, they recall the fashion for lattice ceiling panels that Vasari had imported to Venice. This period was also that of the closest collaboration between Tintoretto and Andrea Meldola. Together they decorated the Zen palace with murals. The fresco technique played an important role in the formation of Tintoretto’s terminology. Because it provided him with the speed of execution on which his pictorial style was based. Unfortunately, only a few prints of his eighteenth-century frescoes and some fragments of the numerous frescoed facades that adorned Venice have survived.Tintoretto’s drawing exercises consisted of nature, statues and small wax models, which were placed in various ways and artificially illuminated, for example in small sets. These methods caught the painter’s interest in solving problems of form and light. The indefatigable painter acquired a storytelling fluency that enabled him to describe, with a steady brush and imaginative inspiration, the series of biblical stories, the mythological episodes of the house of the poet Pietro Aretino in Venice (1545) and sacred compositions such as Christ and the Woman, caught in adultery, in which Characters illuminate large spaces in fantastical perspectives in a distinctive Mannerist style. Tintoretto returned to his former form of composition in The Last Supper at Saint-Marcuola (1547). There, a selection of gritty and folky types manage to underpin the scene with a depiction of everyday life mysteriously affected by a wondrous revelation.

A few months later, Tintoretto caught the attention of artists and literary circles with “San Marco Freeing the Slaves” (also known as “The Miracle of the Slave”). The letter from Altino, full of admiration but also intended to dampen Tintoretto’s youthful vitality, confirmed the reputation of the 30-year-old painter. It doesn’t end there, but one of Altino’s letters contains signs of discord. Although Aretino wrote no more letters of recommendation to Tintoretto, he commissioned him to produce family portraits, and after his death his likeness would appear in Tintoretto’s monumental Crucifixion in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco (1565). The painting “San Marco Emancipates a Slave” is so rich in structural elements of post-Michelangelic Roman art that it can be assumed that Tintoretto visited Rome. However, he does not stop at his artistic experiments. The stories from Genesis, painted for the Scuola della Trinità (1550-1553), show a new attention to Titian’s style of painting and a palpable awareness of nature. The undoubted masterpiece of this period is Susanna’s Bath (c. 1555). The light creates a crystal clear figure of Susanna against a background evoked by a new poetic sensibility. In 1555, Tintoretto, now a famous and popular painter, married the loving and devoted Faustina Episcopi, with whom he had eight children. At least three of them, Marita, Domenico and Marco, learned the trade from their father and became collaborators. Artist on the go and truly creative, Tintlett has spent most of his life in family societies and workshops. However, his biographer’s subtle love of loneliness did not prevent the painter from establishing friendships with some artistic figures. This particular period of Tintoretto’s career – characterized by a greater vibrancy of colour, a penchant for a varied approach and a highly decorative quality – coincided with his growing appreciation for the art of Paolo Veronese, who worked at the Doge’s Palace. . The assimilation and transformation of Veronese elements in Tintoretto’s work can be seen in his beautiful ceiling paintings of biblical stories.

The use of light-absorbing paints opens up new possibilities for proposing spaces that are no longer constructed solely by perspective. In these rooms, the painter rendered the crowds in a symmetrical order with the rest of the painting. This is a feature never before seen in Venetian art. At that time, Tintoretto began decorating the Church of the Madonna dell’Orto and the private chapel of the Contarini family, which in 1563 became the final resting place of the great Cardinal Gasparo.

Tintoretto’s work for Madonna del Orto, which fascinated him for about ten years, also gives us an idea of the evolution of the idiomatic elements of his art. The Anointing of the Virgin Mary in the Temple (c. 1556) was, according to Vasari, “a work of perfection, the best work in its place and the most successful painting”. In The Vision of the Cross of St. Peter and the Martyrdom of St. Paul (1556), the figures stand out dramatically in a hazy, surreal, light-filled space. Two huge canvases, one shows Jews worshiping the golden calf, the other shows Moses receiving the mark of the law and the Last Judgment on Mount Sinai. Tintoretto has made a thematic connection between the two scenes which bears witness to knowledge of the Bible and contemporary spiritual movements. The high formative quality of both paintings suggests that Tintoretto experimented a great deal during this decade. This is evidenced above all by the dramatic way the scene is staged, a style that impresses the viewer with its romantic pathos. Tintoretto’s spatial consciousness has a dynamic character. As contemporary critics have noted, Tintoretto gives the impression that he is sinking forward almost as quickly as he is rising. Contrasting movements give the characters a similar instability. To achieve these effects, Tintoretto always used different formulas: in Christ Healing the Paralytic (Pool of Bethesda) in the Church of San Rocco (1559), the Gospel passage takes place in a compact space through which the truncated ceiling seems to weigh down . Rushing crowd; In San Giorgio and the Dragon, Tintoretto sets the story in a landscape of considerable depth interrupted by the white walls of the city.

A series of canvases commissioned from Tintoretto in 1562 by the philosopher and doctor Tommaso Rangoon, grand custodian of the Scuola di San Marco, contain similar elements. In May 1564, the councilors of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco decided to decorate the Sala dell’Albergo with paintings instead of the movable decorations used on holidays. San Rocco protects against the plague. The numerous epidemics of the time had given new impetus to the cult of the saint and brought great wealth to the scolas, which were a prominent center for the care of the poor and vulnerable. When Tintoretto donated his oval painting of Saint Rochus in Glory to Escola, the directors decided to entrust him with the decoration of the sala. Vasari recalls that the design was invited by several great artists, including Paolo Veronese, but Tintoretto, whose work was already installed in the sala, prevailed over the competition. A similar episode is considered by contemporary sources as evidence that the painter did not regret his work. He was truly a man driven by passion for painting, not financial gain. Because he entrusted himself to a big company with a very low salary.

The question of who helped Tintoretto in his dizzying career remains open. Marietta was only 9 at the time and Domenico was 4 at the time, but it is known that by 1560 young painters, especially from Holland and Germany, began to visit Tintoretto’s studio. In 1565 his colossal crucifix was exhibited in the Sala del Albergo. Around Christ in the center, many figures are bathed in bright light, muting the colors, adding dramatic power to the image. The decoration of the hall was completed in 1567. These included other scenes from the Passion of Christ, known for their thematic innovations. Visiting Venice in 1566 to update his “Life Stories of the Most Eminent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors,” Vasari had the opportunity to follow Tintoretto’s work in progress. No doubt he had the painter’s later work in mind when he wrote that Tintoretto was “the most extraordinary brain that the art of painting has produced”.

Despite all the fundamental reservations about Tintoretto’s style, Vasari felt its grandeur. Around 1575 Tintoretto resumed the decoration of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco with renewed enthusiasm. In time for the saint’s feast day, August 16, he completes the huge central panel of the Upper Room by raising a bronze serpent and promises to paint a series of canvases. Saints and our venerable school for my devotion to the glorious knife San Rocho. In 1581 all the ceiling paintings (ten oval panels and eight diamond-shaped chiaroscuro panels; the latter restored in the 18th century) and ten teleri (large history paintings on canvas) on the walls were completed. In fact, the basic idea goes back to concepts detailed in the rough illustrations of the Biblia paperum, the concordance of the Old and New Testaments.

It does not appear that the painter executed four mythological allegories of the Doge’s Palace in the same year, the most famous of which are those of Bacchus, Ariadne and Venus. They are all very elegant works with an academic finish. But the real Tintoretto can certainly be found in San Rocco. There he presents Bible illustrations to many poor people who, like medieval mosaic painters, participate in charity, testifying to his great faith. His deeply independent faith in religious mythology, without any of the anti-reformation laws, is like the San Trovaso altarpiece of 1577, at the Council of Trento, built for the Doge da Ponte. With women seducing St. Anthony for Meldon, one of the participants and historians of the council.

In 1577 Marietta and Domenico, already officers of the Society of Painters, along with other future artists of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, were able to help their father. The presence of collaborators is certainly evident in two cycles: the eight scenes of the Gonzaga cycle, with vivid scenes of battles, painted between 1579 and 1580, and several paintings for the halls of Scrutinho and Maggiore Consiglio in the palace. Dodges. which the Republic wanted to decorate with new paintings after the fire of 1577. The Doge’s palace was largely down to his workshop.

With canvases made between 1583 and 1587 for the lower room of the Scura Grande di San Rocco, Tintoretto, depicting episodes from the life of Mary and Christ, takes a new direction. Light of the most lyrical meaning dominates the picture, flashes of transparent brushstrokes. The space is coupled with an infinite series of points of view. The landscape sometimes dominates the human figure, as in the two large works in the room on the ground floor. The Virgin Mary of Egypt and Mary Magdalene are immersed in a hazy atmosphere of glowing light, and things come to life with life force. More than ever, Christianity presents a vision of man and the hope of his destiny, and is an invitation to the 70-year-old painter’s life of appreciation. A wonderful model of Paradise for the Doge’s Palace (in the Louvre) and the Last Supper by San Giorgio Maggiore, with inclusive apparitions of divine beings, completed a few months before his death, testify to Tintoretto’s deep spiritual inclination. He died in 1594 and was buried next to Marietta, his favorite daughter, in the Church of the Madonna dell’Orto.

Tintoretto’s Legacy

Tintoretto was a painter of an ever-evolving, completely personal skill and vision. Although his family almost certainly originated in Lucca, Tintoretto (nickname meaning “little dyer” because his father had a profession as a silk dyer or dyer) was a Venetian who was considered a painter. Through Venice and his numerous works, he helped shape the face of the city. He is not only an eyewitness of the city’s life in the development of the sacred and profane complex paintings of Venetian art, but also a representative of the social myth that was part of the dramatic history of Italy in the 16th century.

Tintoretto’s art was much discussed and appreciated in Venice in the years after his death. Above all, it was the sharp assessment of Marco Boschini, the great critic of 17th-century Venetian painting. Roger de Bayles, following the latter, coined the prominent term Tintoretto. But in the eyes of 18th-century critics, as they approached the neoclassical rationalism of the 19th century, Tintoretto’s art seemed excessive and far from sensitive. The Romantic enthusiasm of John Ruskin inaugurated a new approach to Tintoretto’s art, and contemporary art historiography has recognized him as one of the greatest representatives of the vast European movement which sought to interpret according to the great Venetian tradition was done.

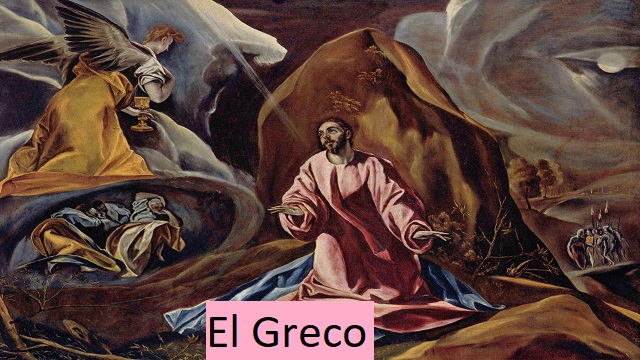

Read also: El Greco